中秋节 Mid-Autumn Festival (Mooncake Festival)

By Wong Tuck Cheong

The Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节 zhong qiu jie), the second grandest festival in China after the Chinese New Year, is so named because it is celebrated on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month, which is always in the middle of the autumn season in China. It is also popularly referred to simply as “Fifteenth of the Eighth Month” (bayue shiwu).

It is also celebrated in other Asian countries like Korea, Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

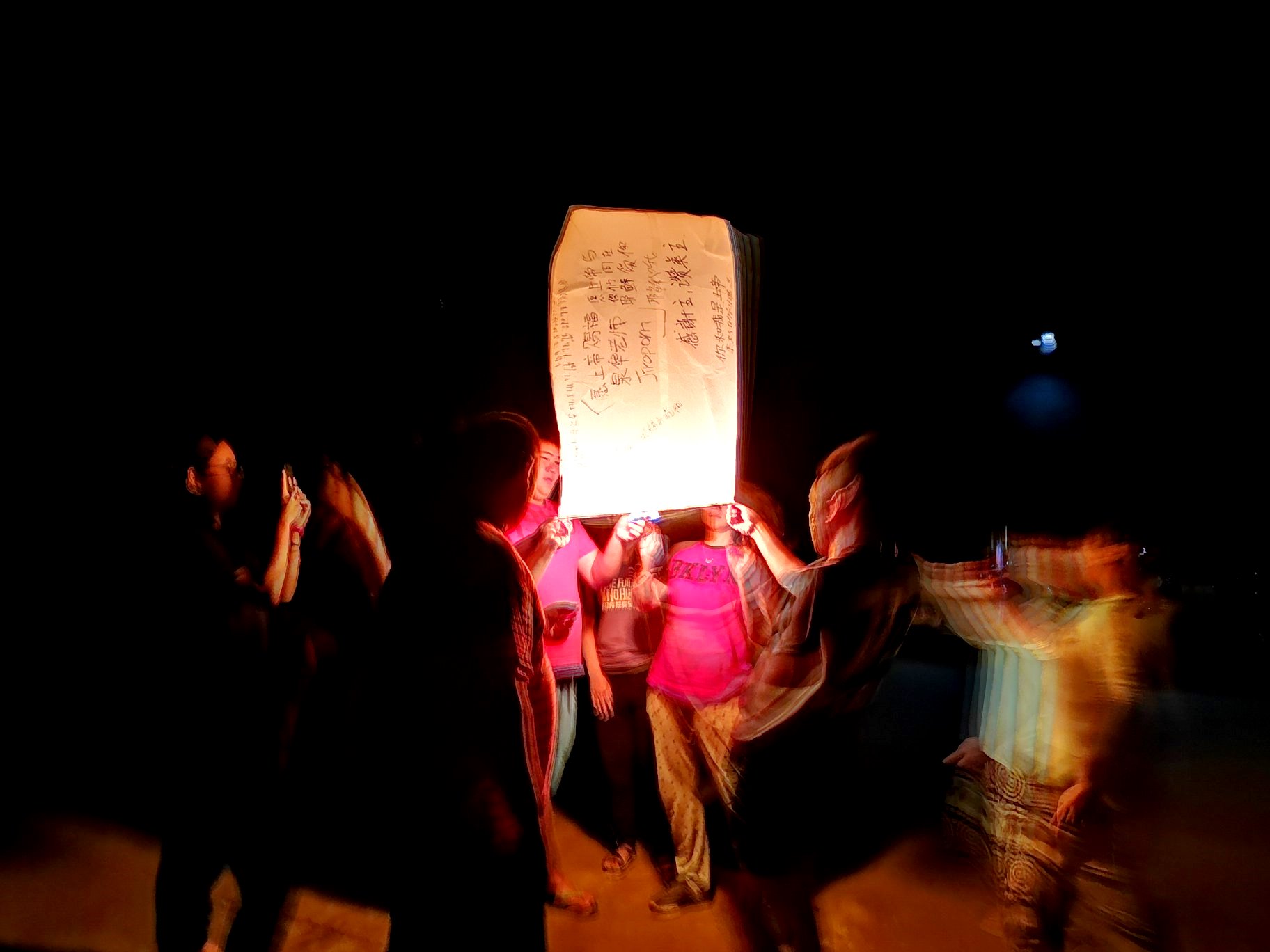

The day is also known as the Moon Festival, as at this time of the year the moon is believed to be at its fullest and brightest. Families will reunite for a sumptuous dinner, worship the moon with offerings of mooncakes, apples, pears, peaches, grapes, pomegranates, watermelons and oranges; and later together enjoy mooncakes and the fruits.

However, the full moon does not always appear on the 15th night. According to the laws of astronomy, the new moon always appears on the first day of a lunar month, but it may appear in the early morning or in the evening of the first day. The time span from the new moon to the full moon is shorter than 15 days. So, if the new moon is in the early hours of the first day, then the full moon will appear on the 15th or even 14th day. If the new moon appears late, you will see the full moon on the 16th day, and sometimes even on the 17th day.

Traditionally, this day is also considered as a harvest festival since fruits, vegetables and grain would have been harvested by this time and food was abundant.